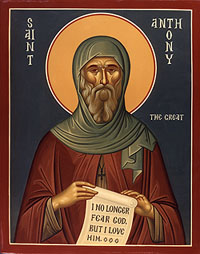

The history of monasticism is usually considered to begin with St. Antony the Great, who lived in the late 3rd and early 4th centuries (AD, of course). Note that this is not the same St. Anthony who Catholics pray to in order to find lost objects, and lived about 900 years later.

|

| Not that St. Anthony of Padua can't come in handy at times |

Antony proceeded to "flee to the desert," in order to avoid all the problems of living within Roman society and simultaneously living as a Christian. He had come to the conclusion that the best way to live the "vita apostolica," or "apostolic life" was to eschew the world as much as possible. According to the Life of Antony, written by St. Athanasius, Antony faced a multitude of temptations, even being attacked by demons on various occasions, and tempted by them on others. Furthermore, unlike many other ascetics, Antony decided to go far into the desert, rather than living just outside of the Roman cities.

Because of his reputation for piety, Antony began to gain a large following, and before long the world that he so sought to leave began to follow him into the wastes outside of Roman Alexandria. The further Antony would retreat, the more his reputation would grow, and the more people would try to join him. In time, Antony created a community of desert ascetics, hermits living according to Antony's teachings, but otherwise fairly isolated from one another. For this reason--along with the fact that his vita, the "saint's life" written by Athanasius, was translated into Latin and saw wide readership throughout the Roman and post-Roman world--St. Antony is usually regarded as the father of monasticism, or even the "first monk."

|

| The monastery founded by Antony's followers after his death, today run by Coptic Christians |

|

| You know the line. |

At this point, we can start talking about St. Benedict and the founding of Montecassino. Benedict was born about a century and a half after the death of Antony as Roman control of western Europe was in collapse, being replaced by the Visigothic Iberia, Frankish Gaul, and Ostrogothic Italy. Like Antony, he was born to a wealthy family, and by the early 6th century he had fled from urban life and began his life as a hermit. When the abbot of a nearby monastery died, the community of monks came and begged Benedict to become their abbot, the leader of the community. He agreed, only to have the monks rebel against his strict rules and try to poison him. The "rules" that the monks so despised have come to be known as the Rule of St. Benedict, and within a few centuries it would be the basis for the running of most monasteries in Western Europe. Until the 20th century it was widely accepted that Benedict created this rule from scratch, though recent research strongly suggests that he was influenced by a number of other important early monastic figures, such as John Cassian. Whoever Benedict drew upon, his subsequent influence on the course of medieval history is undeniable.

Eventually, Benedict grew tired of the monks' political machinations (in addition to trying to poison him several times, they also hired prostitutes to temp and thereby discredit him. Needless to say these monks weren't exactly pious...), and by the 530s he left the community and founded Montecassino, in the mountainside of southern-central Italy.

|

| The monastery today, reconstructed following WWII. I'll talk about its destruction in a future post. |

That should do it for this update! I realize that there's not much about my trip in this post, but it's hard to talk about what I'm doing for the next few months without a common frame of reference. The rest of my updates this week will be about food and wine (I think I'm going to make some rabbit...), and next week's history post should be about what I'm actually doing here (as well as pictures that I haven't just turned up from Google!). Thanks for reading!

Very interesting Frank! I just feel sorry for St. Antony's sister!

ReplyDelete